THE HIGHEST RANKING CANADIAN OFFICER KILLED IN THE GREAT WAR BY FRIENDLY FIRE

Written by Gordon MacKinnon and originally published in Vol 8, Issue 1 of the Canadian Military Journal. Mercer was killed one hundred years ago today.

Deafened by a German artillery barrage, his leg broken by a stray bullet as he tried to move to safer ground, Major-General Malcolm Smith Mercer was fatally wounded by shrapnel from a British artillery counter-offensive trying to prevent the Germans from bringing up reinforcements.

The highest ranking officer of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) to be killed in action in the First World War, General Mercer succumbed to his wounds in the early hours of 3 June 1916 in No Man’s Land at the foot of Mount Sorrel near the ill-fated town of Ypres, Belgium. But for the quick thinking and perseverance of a Canadian corporal sent out to locate and bury soldiers killed in the area, Mercer’s body might have been lost forever in the quagmire churned up by the shelling.

Instead, the general was buried in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery on 24 June 1916 in a full military funeral with all battalions of the Canadian Mounted Rifles represented. He was also posthumously Mentioned in Despatches by General Sir Douglas Haig for his valiant conduct, the third time he was so honoured.1

Except among the Mercer family and students of the Great War, General Mercer’s name is virtually forgotten today. The absence of letters and documents has meant that historians have overlooked the contribution of this hard working, amateur soldier who endeavoured to solve the problems of the new trench warfare of 1914-1916. However, the contents of a diary written by Mercer during the period 22 August 1914 to 10 November 1915 – now part of the collection of the Queen’s Own Rifles Museum – give some insight into the conscientious officer who became the first General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the CEF’s 3rd Division.

Mercer was born on the family farm in what is now north-west Toronto. Until age 25 he worked on the farm, acquiring a high school diploma and then enrolling at the University of Toronto in 1881. He must have felt embarrassed at being older than other first year students because he under-misrepresented his date of birth by three years. The Great Fire at the university in 1890 destroyed the student records, so it is not possible to know exactly when he made the change. Contrary to dates in published biographical sketches, census evidence is conclusive that he was born on 17 September 1856.2

Mercer graduated in 1885 with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy. He then studied law at Osgoode Hall and was called to the Bar in 1888. While at university, he enlisted as a private in the Queen’s Own Rifles of the Non-Permanent Active Militia, a prestigious battalion of volunteers. Mercer did not exploit the social position open to him as an officer as he nonetheless rose steadily through the ranks. However, he did excel at rifle shooting, resulting in several trips, not only to provincial and national competitions, but also to the Bisley Rifle Competition in England – as a competitor, and, in 1909, as the adjutant of the Canadian team. The Queen’s Own Rifles grew to two battalions, and, in 1911, Mercer became Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant, replacing Sir Henry Pellatt, who was promoted to command the 6th Brigade.3 All known portraits of Mercer show him in the uniform of either the Queen’s Own Rifles or the Canadian Expeditionary Force. He stood ramrod straight, six feet tall with dark brown hair and blue eyes, as well as a generous moustache that completely hid his mouth. Most observers noted that, upon first meeting, he created an impression of cool reserve.

Mercer established a comfortable law practice in 1889 with classmate S.H. Bradford that lasted until his death. The contents of his estate, auctioned in 1925, showed him to have been a collector of art, and included European and Canadian paintings, sculpture, porcelain, and antique furniture. Many of the Canadian paintings were by Carl Ahrens,4 whom Mercer had supported financially when Ahrens was a young artist.

Later, a fellow officer described Mercer as “a man who above all else took a sane view of life; quiet and reserved, with a touch of cynical humour but great kindness of heart, he impressed one as a born leader of men.”5 His “even temper, kind and open nature” continued to be noted by his friends and admirers well after his death.

Moonrise Over Mametz Wood by William Thurston Topham. The painting has been described by veterans as “an eerily accurate impression of the Somme battlefield in 1916”. Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, CWM 19710261-0752

The Call to Arms

During the early part of the 20th Century, Canada’s only perceived threat by land was an expansionist United States, and the country had depended upon maintaining good relations with its American neighbours to avoid a repeat of military invasion last seen in the War of 1812, followed by some unofficial armed incursions by the Fenians in 1866. Britain, then in control of Canada’s foreign and defence policy, followed a similar course of action and withdrew its troops in 1871, except for those garrisoned at the Royal Navy base at Halifax.6 Until 1904, by law, the General Officer Commanding the Canadian Militia had to be a British Regular,7 and the few remaining British troops were withdrawn from fortresses only in 1905 when the British decided to cease using Halifax and Esquimalt as naval bases.

The Canadian defence force in 1914 was very small, consisting of 3000 Permanent Force Active Militia and 55,000 Non-Permanent Active Militia, and a navy of just two ships.

…the total authorized establishment of the [Permanent] Force was 3110 all ranks and 684 horses. It…comprised two regiments (each of two squadrons) of cavalry – the Royal Canadian Dragoons and Lord Strathcona’s Horse; the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery with two batteries, and the Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery with five companies; one field company and two fortress companies of engineers; one infantry battalion – the Royal Canadian Regiment; together with detachments of various service and administrative corps. The Permanent Force’s main peacetime functions were to garrison fortresses on either coast and assist in training the militia.8

Entry into the widely anticipated war was never in doubt, and plans to raise quickly a force of 30,000 volunteers had been made before 4 August 1914. However, this 1911 plan to give the commanders of the existing six Military Districts of Canada responsibility for recruiting the overseas battalions was peremptorily changed by Colonel (later Lieutenant-General Sir Sam) Hughes, the Minister of Militia and Defence in Sir Robert Borden’s Conservative government. Hughes initiated matters through a night lettergram to 226 militia commanders, ordering them to recruit volunteers.9 This impractical, impromptu, chaotic methodology eventually had to be modified, but it led to the CEF being composed mainly of numbered battalions, not battalions carrying the names of existing militia units.

Because there were very few professional officers, senior militia officers who appeared to be competent and had the right political affiliations and opinions were given senior appointments within the new CEF. Lieutenant-Colonel Mercer had never seen active service, but he possessed the political and religious qualifications needed to impress the Minister of Militia. He had even accompanied Sir Sam on a pre-war military reconnaissance tour of Europe, resulting in both men concluding that war with Germany was inevitable.10

When Mercer left Toronto on 22 August 1914 for Camp Valcartier, then under construction near Quebec City, he was in charge of the soldiers from the Queen’s Own Rifles. At Valcartier, he was given command of the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade, composed of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4thBattalions recruited in Ontario.

The 1st Contingent of the CEF left Quebec City on 25 September 1914 on a fleet of passenger liners destined for England. Delays in the Gulf of St. Lawrence while waiting to rendezvous with its Royal Navy escort, followed by embarkation of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, compounded with the slow speed of the convoy, resulted in a 20-day journey to Plymouth. One man fell overboard and another was operated on unnecessarily for appendicitis; otherwise, the voyage was undoubtedly as dull as the weather was fine.

The Canadian Contingent was under the command of Colonel V.A.S. Williams, one of the few Permanent Force officers on board. This Permanent Force officer shortage was due to the fact that the Royal Canadian Regiment had been sent to Bermuda on 6 September to release a British Regular unit, the 2nd Battalion, The Lincolnshire Regiment, for deployment in Flanders.11 Williams, a graduate of the Royal Military College, Kingston, and the Adjutant-General of the Canadian Militia, would ultimately play a role on Mercer’s last day.

Winter in the Mud and Rain

Upon arrival at Plymouth, a British Regular, Lieutenant-General E.A.H. Alderson, who had been appointed after previous Canadian government consultation, took over command before the troops disembarked.12 Mercer was placed in command of Bustard Camp on Salisbury Plain near Stonehenge. The troops resumed the routine commenced in Canada that would continue their transformation from civilians into professional soldiers: route marching and physical exercises for fitness, and entrenching, bayonet drill, musketry and other instruction to improve their military skills. The conditions were appalling. The rapid expansion of the British forces meant that there was no extra barrack accommodation. Consequently, the Canadians were housed in tents. Contractors were building huts, and hundreds of carpenters and bricklayers were seconded from the Canadian Contingent to speed up construction.13 Slowly, the troops were moved into the huts or were billeted in private homes in the small villages nearby. There was never enough space, however, and Mercer’s brigade was the only one that spent the entire winter under canvas. Several severe storms blew down most of the tents and marquees. It rained 89 out of the 123 days that they were so quartered. Surprisingly, the health of the troops remained good, and those in huts and billets suffered more illness than those in tents.14

The 1st Canadian Contingent was renamed the 1st Canadian Division, and British staff officers were added to this largely amateur army. Inspections were frequent, and Mercer must have felt satisfaction when, after a Royal Inspection on 4 November 1914 by King George V and Queen Mary, accompanied by Field Marshal Lord Roberts (who was Honorary Colonel of the Queen’s Own Rifles at the time) and Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, he recorded their comments in his diary: “No finer physique in the British Army. A fine brigade. Splendid.”15

Major-General Malcolm Smith Mercer as General Officer Commanding of the CEF’s 3rd Division. Courtesy of the Woodstock Museum NHS.

Mercer Takes Command and Learns on the Job

All three brigade commanders of the 1st Division had spent many years in the Canadian Non-Permanent Active Militia, but only Brigadier-General R.E.W. Turner, VC, DSO, had combat experience. He had won his decorations as a lieutenant in the Royal Canadian Dragoons during the South African (Boer) War. Turner was the GOC of the 3rd Brigade, and, for a brief time, was also GOC of the 2nd Division. Controversy over his eventual handling of the Battle of St. Eloi Craters (June 1916) would result in his transfer to a staff position in England. Brigadier-General Arthur W. Currie, a Vancouver real estate broker and speculator, commanded the 2nd Brigade. He would later become commander of the Canadian Corps, earning a reputation as one of the war’s outstanding allied generals. Mercer had been in the Queen’s Own Rifles (QOR) for more than 30 years, but had never led troops in battle. The brigadier-generals and their soldiers would just have to learn on the job.

Four days before the brigade embarked for France on 9 February 1915, Mercer was promoted to full colonel.16 The training routine intensified in France and Belgium, where units of Canadians were placed in the front line at Armentières, along with experienced troops of the British 4th and 6thDivisions. Then the Canadians moved into the trenches at Fleurbaix, where their role was to hold the trenches defensively while the British 1st Army attacked at Neuve Chapelle. Mercer received another promotion on 2 March, this time to temporary brigadier-general. The brigade was at the Fleurbaix front from 1 to 24 March. Rotations of four days each in the trenches interspersed with four days in reserve billets resulted in the troops enduring 16 days and nights in the trenches. As it materialized, neither side attacked. However, Mercer demonstrated that he was not a ‘château general’ – to understand fully the conditions his soldiers endured, he visited the trenches on 16 occasions and the billets on five.17 After 1 April, the 1st Canadian Division took over four kilometres of trenches north of Ypres, where the British were assuming more of the line from the French. Training and inspections continued. On 12 April, Mercer records that General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, commander of the 2nd British Army, under whose orders the 1st Canadian Division operated, complimented him and the troops, saying that, “for steadiness and precision this Brigade was the finest Salute he had ever seen.”18

Although fatal casualties at Fleurbaix totalled only one officer and 29 men, the Ypres Salient was to be a much more lethal introduction to war. On 22 April 1915, for the first time in warfare, an enemy attacked using clouds of poison gas. The French colonial troops on the left flank of the Canadians were hardest hit by the gas and fled in panic, but the untested 2nd and 3rd Canadian Brigades filled in the gap and held despite the lack of any better protection from the gas than urine-soaked cloths.19 Mercer’s 1st Brigade was in Divisional Reserve in Vlamertinghe. Its 2nd and 3rd Battalions were transferred to the 3rd Canadian Brigade at 2130 hours on 22 April. Early on the morning of 23 April, Mercer was ordered to march the 1st and 4th Battalions across the Yser Canal, and attack in the direction of Mauser Ridge west of Kitcheners Wood. The attack failed for several reasons: there was little time for planning and coordinating the British, French and Canadian forces involved, and the Canadian troops had never attacked before. French troops failed to advance along the canal on the Canadians’ left flank and, in the same area, Geddes’s Detachment of British battalions under Colonel A.D. Geddes, commanding officer of The Buffs, 2nd East Kent Regiment, was attached to the Canadian Division, but was not under Mercer’s command.20 Mercer, with only two battalions at this time, had a complete brigade headquarters staff. Geddes had four to seven battalions but almost no staff. Of note, Colonel A.F. Duguid, in his official history of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, infers reluctance by the British to put a Regular colonel under orders of a Canadian militia brigadier-general.

[Mercer]…could have handled several attached battalions with ease. On the other hand Colonel Geddes was a regular officer, a graduate of the Staff College, and tried in the 1914 campaign. It may be noted that no regular British battalion was in the line under a Canadian brigadier during the battle.21

There were casualties of over 400 in each battalion, and the remnants of the 1st and 4th Battalions withdrew to Wieltje on the afternoon of the 24th. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions continued to fight under General Turner’s command on 24 April when another gas attack was launched. During the evening of the 25th, the 1st and 4th Battalions marched west across the canal, and the 2nd and 3rdBattalions rejoined the brigade at night. The 3rd Battalion, partly composed of men from the QOR, reported more than 400 men captured.22 On 28 April, the entire 1st Brigade was again under Mercer’s command, guarding the canal bridges and in billets for reorganization.23 For their conduct under fire, he and the three other Canadian brigadier-generals were named Companions of the Order of the Bath (CB) by King George V in his Birthday Honours List of June 1915. The award is given for military service of the highest calibre and only 144 military CBs have ever been awarded to Canadians.24

After two weeks of refitting and adding reinforcements, Mercer’s brigade marched southeast to Festubert, where it relieved the 3rd Brigade in the front line on 22-23 May. A company of the 3rdBattalion assaulted from the Orchard on the night of the 24th. A shortage of troops caused by casualties sustained at Ypres made it necessary to use the dismounted Canadian Cavalry Brigade under Brigadier-General J.E.B. Seely as additional infantry in this attack.25 In spite of further heavy casualties, no real progress was made. By the end of the month, Mercer’s brigade was back in billets in Béthune. On 10 June at Givenchy, a short distance from Festubert, the 1st Brigade relieved the 3rd Brigade in the trenches and was to be the main Canadian formation in the attack that began on 15 June.26 For the first time in battle, they would use the Lee-Enfield rifle in place of the Canadian-made Ross rifle that had caused problems in previous engagements. The Ross was an excellent target rifle, but could not stand up to rapid fire with British-made ammunition in muddy conditions.27 While more time was available for planning the assault, a shortage of shells and strong German resistance doomed the action. On the following day, an attack by the 3rd Battalion ran into heavy machine gun fire and was forced back into its own trenches. On the 17th, the 1st Brigade was relieved, moving back into billets. Mercer had protested to General Alderson that orders for Canadian troops to man the front trenches while a mine was exploded under the German lines were both dangerous and unnecessary. He was overruled, and subsequently, there were many casualties.28 By this time, Mercer was developing a reputation as a general who frequently visited his troops in the front line trenches to assess the situation for himself, and as one who was concerned about his soldiers’ welfare.29

At the end of June, the Canadian Division was sent to a ‘quiet’ section of the line near Ploegsteert; quiet only in comparison to the active areas they were leaving. The brigade received reinforcements and continued to integrate the new men through marching and training. Mercer notes that Field Marshal Sir John French, the commander-in-chief of the British forces, inspected the brigade on 14 July and was “very eulogistic on the quality of the Canadian troops at Ypres, Festubert, and Givenchy.”30

Back in Canada, enlistment continued vigorously. More troops had arrived in Britain; a second division had been formed and sent to France at the end of September 1915. This resulted in the creation of the Canadian Corps, with Lieutenant-General Alderson as General Officer Commanding (GOC). Major-General Currie became GOC of the 1st Division, and Major-General Turner took over as GOC of the 2nd Division.31 A third division was planned, and Mercer notes in his diary that on 23 September, “Gen A called – said he had a new position in prospect for me.”32 On 19 October, Alderson told him that he was being recommended for the position of GOC of the Corps Troops from which the 3rd Canadian Division was to be formed.33 The official notice of the appointment was issued on 22 November. Mercer subsequently was struck off strength of the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade on 4 December and appointed GOC 3rd Division with the temporary rank of major-general.34 Thus, the GOCs of the three Canadian divisions had risen from lieutenant-colonels in the Non-Permanent Active Militia to major-generals in the Canadian Corps within 14 months. They had earned quick promotions, not only because of their achievements, but also because the Canadian government insisted that Canadians be promoted to command positions in their own army.

No Man’s Land by Maurice Cullen. This was the drab reality of the Western Front. It was also where General Mercer would die. Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, CWM 19710261-0134

A Last Reconnaissance in the Trenches

When the 3rd Division was formed in December 1915, “…the six regiments of Mounted Rifles [CMR] were converted into four battalions of infantry, making the 1st, 2nd, 4th and 5th Battalions of the 8thBrigade under Brigadier-General Victor A.S. Williams.”35 They were holding the line at Mount Sorrel on 1 June 1916. The 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles (CMR) held Trenches 47-53 on the brigade right, and the 1st CMR held Trenches 54-60 in the left sector up to Sanctuary Wood; while the 2nd and 5th CMR were being held in brigade reserve at Maple Copse. On 1 June, the Germans dug a trench joining the heads of the saps they had made opposite Trenches 51 and 52.36 As an aside, Lieutenant-General Sir Julian Byng had been appointed GOC of the Canadian Corps a few days before on 28 May to replace Alderson.37 Under Byng’s command, the CEF was to develop into a formidable fighting force.

On the 1st June, he [Byng] visited Major-General Mercer, who explained the situation at Mount Sorrel and Tor Top [Hill 62]. General Byng then told Major-General Mercer that he wanted him to carry out a reconnaissance with a view to a local operation to improve it. Later he went round all the headquarters in front of Ypres. Whilst he was at 8th Brigade headquarters, Major-General Mercer came to make arrangements with Br-General Williams for this reconnaissance, and asked General Byng if he would come. After a considerable pause, General Byng said. “No. You had better go yourselves tomorrow and make your own proposals. I will come around and see them on Saturday.”38

Major-General Mercer and Brigadier-General Williams met the Commanding Officer of the 4th CMR, Lieutenant-Colonel J.F.H. Ussher, in his battalion headquarters, “…in a dug-out in the immediate support trench, about twenty-five yards back of the front line”39 to evaluate the situation. Just as the generals had completed their inspection of the 4th CMR trenches, German artillery smashed the 3rd Division’s front from 0830 hours to 1300 hours with the most intense bombardment witnessed up to that time. A shell explosion deafened Mercer and seriously wounded Williams in the face and head. Mercer’s Aide de Camp, Captain Lyman Gooderham, was knocked unconscious briefly but was not wounded. Williams was taken to the dressing station in a long, narrow tunnel that had two entrances: one a shaft dug from the communication trench known as O’Grady Walk, and the other in a shelter trench called the Tube. Mercer, Ussher, and Gooderham remained in the 4th CMR headquarters.40 Ussher went to the tunnel to check on the condition of General Williams and was trapped when enemy shelling blocked both exits. The German infantry occupied Mount Sorrel above after detonating four mines.41 Gooderham attempted to move Mercer from the headquarters dugout to safety across the open stretch, since all trenches had been flattened. In the process, a random bullet broke Mercer’s leg. Gooderham bandaged the wound and the two men sheltered in a ditch. That night, British artillery fired shrapnel shells to prevent the Germans from bringing up reinforcements. Gooderham, who had stayed with the general throughout this ordeal, recorded that between 0100 hours and 0200 hours on 3 June, shrapnel from these British guns pierced the general’s heart and caused his instantaneous death.42 He was three-and-a-half months short of his 60th birthday.

Major-General Currie had learned from earlier battles that saturation artillery bombardment was essential to infantry success. Employing this technique with some innovations, his 1st Division recaptured the lost ground within one hour on 13 June 1916. “The first Canadian deliberately planned attack in any force” states the British Official History, “had resulted in an unqualified success.”43 Several German counterattacks were defeated, and the fighting ended in a stalemate typical of trench warfare.

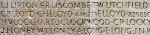

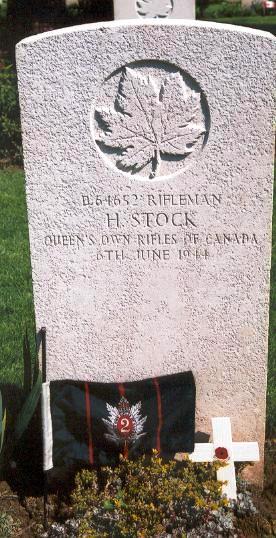

PA 004356 The grave of Major-General Mercer.

Recovering the Body

Corporal John Reid of the 4th Battalion was one of a group of men assigned to explore No Man’s Land at night, tasked to locate and bury soldiers who had been killed in the German attack of 2-3 June. On the night of 21 June, his party found and buried approximately 30 corpses.44 Corporal Reid’s letter describing the finding and recovery of General Mercer’s body was published subsequently in a Toronto newspaper.

… I was examining bags of stuff that had been taken off the dead the night before when I came across a pass with “General Mercer” signed on it. Just think of the excitement then, as we believed he was in the hands of the Hun. I called Pioneer Range, as we were together out searching the night before and he said that must be the spot where they opened the machine gun on us…The real excitement then started for we were spotted as soon as we left the dugout and [it is] thanks to some shell holes that we ever got there. They were not contented putting the machine guns on us. They even sent coal boxes [heavy shells] over, and some near ones too. Anyway, by six o’clock, we got the body dragged to a shell-hole about five yards from where we dug it out, where it had been buried except one boot and about four inches of a leather legging sticking out of the mud. That disinterring was really the worst part of the lot, as we had to lie face down and scratch until we got the General’s body uncovered, and then we searched the body again and saw the epaulets with crossed swords and star. I then cut off the General’s service coat and placed the body in a shell-hole till after dark.45

Williams, Ussher, and Gooderham had all been captured by the Germans and became prisoners of war.46 Sir Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook) wrote at the time of Mercer’s death: “It is tragic to think that such a brilliant soldier, who had risen to the command of a division by sheer force of ability, should have died just as his new command was going into its first big action and needed his services so greatly.”47

Equally tragic, perhaps, was the fact that the fatal injuries Mercer suffered in the opening bombardment in the first major battle fought by his 3rd Division makes it impossible to evaluate his tactical competence. Organizational ability and hard work were his contributions to the development of the formidable Canadian Corps. He organized the 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade out of partly trained amateur soldiers, and then trained it so that it was able to withstand the first shock of battle at Second Ypres. He took 12 battalions of partly trained troops, of whom only the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry had much front line experience, and from them created the 3rd Canadian Division, which, under his successor, was to become one of the best combat divisions in the British forces.

Gordon MacKinnon, MA, a retired Toronto high school history teacher, served as a teacher and vice principal in Department of National Defence Schools Overseas, Metz, France, 1962-1966.

NOTES

- At this time, the only valour awards that could be made posthumously within the British honours system were the Victoria Cross and the Mention in Despatches.

- Census of 1861, District 3 Township of Etobicoke, p .37. Census of 1871, District No.13 South Oxford, Sub-District A, Township Dereham, Division No. 3.

- Lieutenant-Colonel W.T. Barnard, The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada 1860-1960 (Don Mills, Ontario: The Ontario Publishing Company, 1960), p. 104.

- Catalogue of Highly Important old and modern Pictures and Drawings, Piranesi etchings, fine old Delft Pottery…and works of Art of the Late Maj.-Gen. Malcolm S. Mercer C.B., …under Instructions from Executors, Toronto, Jenkins Galleries, 1928. Toronto Reference Library, 708.11354 J25

- University of Toronto Archives, [UTA] A73 0026/318/43.

- Desmond Morton, Understanding Canadian Defence (Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2003), p. 32.

- Colonel G.W.L. Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1919 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1962), p. 8.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Ibid., p. 6.

- J.E. Middleton, Municipality of Toronto: A History, Vol. 2 (Toronto & New York: Dominion Publishing Company, 1923), p. 39.

- Nicholson, p. 24.

- Colonel A.F. Duguid, Official History of The Canadian Forces in the Great War 1914-1919, Vol.1 (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1938), p. 120.

- Ibid., p. 137.

- Ibid., p. 142.

- Unpublished manuscript diary of M.S. Mercer, 22 August 1914-10 November 1915, QOR Museum, Casa Loma, Toronto, 4 November 1915. Hereafter referred to as ‘Mercer’s Diary’. No diary for 11 November 1915 to his death on 3 June 1916 is known to have survived.

- Ibid., 5 February 1915.

- Ibid., March 1915, passim.

- Ibid., 12 April 1915.

- Tim Cook, No Place to Run – The Canadian Corps and Gas Warfare in the First World War(Vancouver: UBC Press, 1999), p. 25.

- Nicholson, p. 67.

- Duguid, p. 266. The Buffs had a regimental association with the QOR. Colonel Geddes was killed on 28 April 1915.

- Mercer’s Diary, 25 April 1915.

- Ibid., 28 April 1915.

- Veterans Affairs Canada website http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/general/

- Nicholson, p. 102.

- Mercer’s Diary, 10 June 1915.

- Ibid., 13 June 1915.

- Ibid., 16 June 1915. On 6 July 1915, he protested orders that 200 of his exhausted men be employed as a working party. On 7 August he records his indignation when his men are kept waiting for an inspection that had been cancelled without informing them.

- General Mercer was in the trenches nearly every day that his troops were in the front line. During the period from 1 March 1915, when Mercer’s 1st Canadian Brigade assumed active control of front line trenches, until 10 November 1915, when his Personal Diary ends, Mercer records 57 personal visits and inspections of trenches held by troops under his command. Mercer’s Diary, passim.

- Ibid., 14 July 1915.

- Nicholson, p. 115.

- Mercer’s Diary, 23 September 1915.

- Ibid., 10 October 1915. The promotion was announced in the London Gazette, 21 December 1915.

- Personnel Records Envelope, LAC RG150 Box 6121-45, Casualty Form.

- Captain S.G. Bennett, The 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles 1914-1919 (Toronto: Murray Printing Company Limited, 1926) p. 12.

- War Diary 1st CMR, 2 June 1916, War Diary 2nd CMR, 1 June 1916, War Diary 4th CMR, 1-2 June 1916, War Diary, 5th CMR, 1 June 1916.

- Jeffrey Williams, Byng of Vimy, General and Governor-General, (London: Leo Cooper, 1983), p. 120.

- Brigadier-General Sir James E. Edmonds, History of the Great War Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916 (London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd., 1932) p. 231, fn.1. There is no source cited for Byng’s statement.

- J. Castell Hopkins, Canada at War 1914-1918 (Toronto: The Canadian Annual Review Limited, 1919) p. 146.

- War Diary 4th CMR, June 1916, pp. 3, 4, 5.

- Hopkins, p. 148.

- Letter from Lyman Gooderham to Professor Oswald Smith, University of Toronto Archives, UTA A73 0026-318/43.

- Quoted in Nicholson, p. 136.

- The 8th Brigade’s casualties for the battle of 2-3 June were 74 officers and 1876 ORs.

- The Globe, Toronto, 15 July 1916, p. 9, ‘Signed Pass Permit Finds General’s Body – Corporal Reid Tells Dramatic Story of Locating Remains of Gallant Mercer.’ There is no mention of this event in the 4th Battalion War Diary.

- The three officers were released in prisoner exchanges before the end of the war. Williams returned to Canada in late 1918 and was promoted to major-general in command of Military District 2 based in Toronto. The most senior Canadian to become a POW, he died in 1949 at the age of 82.

- Lord Beaverbrook, Canada in Flanders,Vol.II, (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1917), p. 175.