by guest author Capt. B. E. Taylor, CD, MA (Ret’d)

Note that this was originally written as a university course paper and consequently follows a fairly rigid referencing protocol.

War memorials are meant to commemorate the sacrifices that have preceded their erection. Particularly for those commemorating the dead of the Great War, they address “some of the complex issues of victimhood and bereavement.[1] “Glory, the reward of virtue” is a translation of the Latin inscription on a carillon bell in the University of Toronto’s Soldiers’ Tower, which commemorates the university’s war dead,[2] and suggests a linkage between sacrifice and redemption.

Soldiers’ Tower is evidence that government (at all its levels) and the state are not, nor should they be, the only sources of memory and mourning. The human sacrifices of war “should never be collapsed into a set of stories formed by or about the state,” and the erection of local and private war memorials helps to bring a local context to the lesions brought by total war.[3]

Other examples in Toronto of such non-public monuments include the war memorials of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada and the 48th Highlanders of Canada. Both units perpetuate overseas battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada Memorials

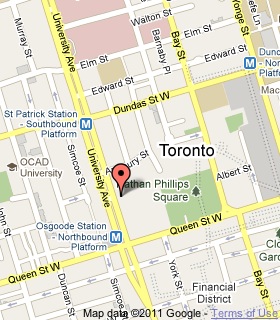

Under the chairmanship of Sir Henry Pellatt, the Q.O.R. Ex-Members’ Association was formed October 1, 1916 on his initiative with the primary purpose of sending food and clothing to men of the QOR battalions overseas who had become prisoners-of-war. It fell dormant after the war but was revived March 8, 1922 with Major General W. D. Otter acting as Chairman, and by March 1923 a Memorial Building Fund had been established. A decision was made to construct a monument in Queen’s Park instead of erecting a building. That was logical, as the regiment was headquartered just down the street at the University Avenue (Toronto) Armoury located between Armoury and Queen Streets.

Later still, with the approval of the Rector and Wardens of St. Paul’s Anglican Church, 227 Bloor St. East, it was decided that a regimental memorial would be built at St. Paul’s, the Regimental Church.[4] That conveniently obviated the need to find a site for a suitable monument, particularly given that the 48th Highlanders already had a monument in Queen’s Park.

Financing was handled by The Queen’s Own Rifles Memorial Association, a special body created early in 1928 with Brigadier-General J. G. Langton as its President. The most publicly visible part of the memorial, a Cross of Remembrance, was unveiled and dedicated by the Rector of St. Paul’s, a former regimental chaplain, on October 18, 1931[5].

In its churchyard setting the widely recognizable regimental Cross of Sacrifice speaks for itself as a memorial to those who fought and died during the Great War (and subsequent actions).[6] The memorial cross is modelled after the Cross of Sacrifice designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield for the Imperial War Graves Commission (now Commonwealth War Graves Commission) in 1918 that is a part of Commonwealth war cemeteries containing 40 or more graves. The Cross is the most imitated symbol used on Commonwealth memorials[7] .

In its churchyard setting the widely recognizable regimental Cross of Sacrifice speaks for itself as a memorial to those who fought and died during the Great War (and subsequent actions).[6] The memorial cross is modelled after the Cross of Sacrifice designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield for the Imperial War Graves Commission (now Commonwealth War Graves Commission) in 1918 that is a part of Commonwealth war cemeteries containing 40 or more graves. The Cross is the most imitated symbol used on Commonwealth memorials[7] .

Like the original, the QOR cross has a bronze longsword, blade down, mounted on the front of the cross and sits atop an octagonal base. The Latin cross represents the faith of the majority of the dead and the sword indicates the military nature of the monument.[8] The Cross is constructed on granite, with reproductions of the regimental and battalion badges on the base and the battle honours from two world wars[9] represented on the plinth and sub-base[10].

Inside the church is a small chapel to the rear of the main chancel (west side), dedicated on March 13, 1932. A carved alabaster table stands on a granite platform (Plate 8) with a glass-topped bronze casket containing the Book of Remembrance atop it. The names of all QOR soldiers who lost their lives in their country’s service from the Fenian Raid of 1866 to the Korean War are inscribed in the Book.[11]

At each church service at which the regiment is on parade a special party of officers and non-commissioned officers escorts the book to the front of the church. It is presented to the Commanding Officer, who hands it to the Rector, and it is placed on the alter during the service. The book is returned to its place of honour at the conclusion of the service.[12]

There being no colours because the QOR is a Rifle Regiment, the Book of Remembrance is the symbol of the regiment’s honour and the memory of “Fallen Comrades,”[13] held by the Church wardens for safekeeping. Parading the book before the regiment shows the Wardens have fulfilled their trust and that the care of the book and honour are in the hands of all ranks of the regiment. The Commanding Officer’s handling of the book symbolizes his personal responsibility and its return to the Wardens symbolizes their acceptance of responsibility for safekeeping.[14]

48th Highlanders of Canada Memorials

As with the Queen’s Own memorial, a general aversion toward war prevalent in the 1920s and early 1930s influenced the design of the 48th Highlanders monument and neither is suggestive of a spirit of militarism. Their inspiration was clearly mourning the dead rather than celebrating military achievements. Neither mimics Victorian battle monuments nor relies on images from archaic allegory.[15]

A regimental memorial designed by Capt. Eric W. Haldenby[16] was unveiled by Governor-General Baron Byng at the Armistice Day parade in 1923. The granite column which marks the deaths of 61 officers and 1,406 non-commissioned officers and men of the regiment, was funded by friends, members, and former members and raised during the previous summer. Unlike reliance on an almost universal form for Great War monuments (the Cross of Sacrifice), the 48th Highlanders memorial tried for an aesthetic that would combine a geometric abstraction and a figurative realism (Plate 9). The obelisk was also an accepted part of the funerary sculpture lexicon.[17]

The 48th Highlanders monument stands at the north end, or head, of Queen’s Park and looks up Avenue Road.[18] That location was ideal because like the Queen’s Own, the 48th Highlanders were located in the University Avenue Armoury to the south. The boulevard opposite the armoury already had several monuments, including the Sons of England Roll of Honour, also unveiled in 1923,[19] and the South African (Boer War) Memorial at the Queen Street intersection[20].

The 48th memorial site in Queen’s Park was selected because it would be viewed by all south-bound traffic on Queen’s Park Circle as the roadway splits around the park. The monument has replicas of the Regimental crest carved on each side. These bear the words “15th Canadian Battalion,” “134 Overseas,” and “92 Overseas” on the south, east, and west sides, respectively. A carving of a Christian Cross of Sacrifice tops each side.

An inscription on the (north) face reads: “DILEAS GU BRATH 1914-1918 To the glorious memory of those who died and to the undying honour of those who served—this is erected by their Regiment—the 48th Highlanders of Canada”[21] (Plate 11). A scabbarded sword is also carved into the stone. Just as with the QOR Cross of Sacrifice, the 48th Highlanders’ battle honours are inscribed around the monument’s faces[22].

Unlike the Queen’s Own Rifles’ memorial, the 48th Highlanders’ tribute to its fallen is divided between the public monument and a separate accolade in its regimental church elsewhere. Having split twice over issues in the Church of Scotland and relocating the congregation, St. Andrew’s Presbyterian remained the core of the Town of York’s first Church of Scotland congregation and has been the Highlanders’ regimental church since their founding in 1891.

St. Andrew’s follows the “reformed/ Presbyterian tradition”[23] in worship, of which chapels or shrines like those at St. Paul’s Anglican are not a big part. Consequently, the regiment’s other memorial at the regimental church is a communion table in the chancel, dedicated on November 11, 1934. The sergeants of the regiment donated the table in memory of their fallen comrades in World War I and it is now a memorial to the fallen in two world wars and used at every celebration of Holy Communion.

The oaken table was created by Dr. John A. Pearson,[24] a St. Andrew’s congregant. There are abutments, about six inches lower, at the ends of the table, and each has an oak top with a plate of glass set into a (lockable) hinged frame. An inner shelf is approximately 10 inches below the glass on each side, on which lie records. Like the Queen’s Own Rifles, the 48th Highlanders have a Book of Remembrance.

The right-hand abutment of the communion table contains 25 loose leaf pages listing the names and ranks of 1,818 48th Highlanders dead from the two world wars. Two pages, with about 120 names in block script, show when the book is open. The left-hand abutment contains the title page and dedication of the Book of Remembrance on parchment . The regimental crest and St. Paul’s words “Wherefore take unto you the whole armour of God that ye may be able to withstand in the evil day and having done all to stand” are carved on the left table abutment.

The right-hand abutment of the communion table contains 25 loose leaf pages listing the names and ranks of 1,818 48th Highlanders dead from the two world wars. Two pages, with about 120 names in block script, show when the book is open. The left-hand abutment contains the title page and dedication of the Book of Remembrance on parchment . The regimental crest and St. Paul’s words “Wherefore take unto you the whole armour of God that ye may be able to withstand in the evil day and having done all to stand” are carved on the left table abutment.

Conclusion

First World War memorials such as those of the Queen’s Own Rifles and the 48th Highlanders were built in an age of meaninglessness stemming from the recent war and serve to mark the value of individuals. They are not primarily “grand architectural monuments” (Plate 15) but continue a practice in countries of the Empire and Commonwealth of commemorating their role in 20th century conflicts, but without necessarily a sense of the waste and futility of war.[25] They stand as evidence that mourners in the postwar period would not have favoured memorial aesthetics that were pure abstraction. In a sense, they mark for us “a sense that everything is over and done with, that something long since begun is now complete.”[26]

References

Barnard, William T. The Queen’s Own Rifles 1860-1960. Don Mills: Ontario Publishing Company Limited, 1960.

“Battle Honours of the Canadian Army – The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada.” The Regimental Rogue. Accessed June 8, 2020. http://www.regimentalrogue.com/battlehonours/bathnrinf/06-qor.htm

Beattie, Kim. 48th Highlanders of Canada 1891-1928. Toronto: 48th Highlanders of Canada, 1932.

“Book of Remembrance,” The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada Regimental Museum and Archives. Accessed June 8, 2020. https://qormuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/book-of-remembrance.jpg

“Books of Remembrance 1,” 15thbattalioncef.ca. Accessed June 8, 2020. http://15thbattalioncef.ca/commemoration/books-of-remembrance-1/

Bradbeer, Janice. “Once Upon A City: Creating Toronto’s Skyline.” Toronto Star, March 24, 2016.

“Canadian Volunteer Memorial.” The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada Regimental Museum and Archives. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://qormuseum.org/history/memorials/canadian-volunteer-memorial/

Charlebois, Marc. “A Skirmisher from The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada at the Cross of Sacrifice.” Pinterest.ca. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/540220917773385972/

“Communion Table St. Andrew’s Church.” Centre for Distance Learning and Innovation. Accessed June 17, 2020. https://www.cdli.ca/monuments/on/toronto48b.htm

“Cross of Sacrifice.” Wikia.org. Accessed June 17, 2020. https://military.wikia.org/wiki/Cross_of_Sacrifice

“Cross of Sacrifice.” Wikipedia. Accessed June 7, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cross_of_Sacrifice

Farrugia, Peter. “A Small Truce in a Big War: The Historial de La Grande Guerre and the Interplay of History and Memory.” Canadian Military History 22, no. 2, (Spring 2013): 63-76.

“Forever Faithful.” 15thbattalioncef.ca. Accessed June 17, 2020. http://15thbattalioncef.ca/category/uncategorized/

Gough, Paul. “Canada, Conflict and Commemoration: An Appraisal of the New Canadian War Memorial in Green Park, London, and a Reflection on the Official Patronage of Canadian War Art.” Canadian Military History 5, no. 1, (Spring 1996): 26-34.

“Haldenby, Eric Wilson.” University of Toronto Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://alumni.engineering.utoronto.ca/alumni-bios/haldenby-eric-wilson/

“Historic Toronto,” Tayloronhistory.com. Accessed June 8, 2020. https://tayloronhistory.com/tag/boer-war-monument-toronto/

“John A. Pearson.” Wikipedia.org. Accessed June 8, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_A._Pearson

Kimber, William. “Hart House and Soldiers’ Tower.” Accessed June 16, 2020. https://www.flickr.com/photos/35005631@N02/3533747177

Laye, Tim. “Toronto – 48th Highlanders.” Ontario War Memorials. Accessed May 11, 2020. https://ontariowarmemorials.blogspot.com/2013/08/toronto-48th-highlanders.html

Nora, Pierre. “General Introduction: Between Memory and History” in Realms of Memory vol. I trans. Arthur Goldhammer, New York: Columbia University Press, 1992.

Pierce, John. “Constructing Memory: The Vimy Memorial.” Canadian Military History 1, no. 1 (1992): 3-5.

“Queen’s Own Rifles Association.” Qormuseum.org. Accessed June 8, 2020. https://qormuseum.org/history/queens-own-rifles-association/

“Regiment Info.” Canadian Armed Forces. Accessed June 8, 2020. http://48highlanders.com/01_00.html

“St. Andrew’s Church (Toronto). Sensagent Corporation. Accessed June 8, 2020. http://dictionary.sensagent.com/St._Andrew%27s_Church_(Toronto)/en-en/

“Soldiers’ Tower Carillon Inscriptions.” University of Toronto. Accessed May 11, 2020. https://alumni.utoronto.ca/alumni-networks/shared-interests/soldiers-tower/carillon-inscriptions.

“Sons of England Memorial.” Centre for Distance Learning and Innovation. Accessed June 8, 2020. https://www.cdli.ca/monuments/on/tsons.htm

“South African War Memorial (Toronto).” Wikipedia. Accessed June 17, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_African_War_Memorial_(Toronto)#/media/File:South_African_War_Memorial_Toronto_Nov_08.jpg

Strachan, Hew. 2013. The First World War. New York: Penguin Books.

“The 48th Highlanders Monument Queens Park.” Centre for Distance Learning and Innovation. Accessed June 8, 2020. https://www.cdli.ca/monuments/on/toronto48.htm

“Weekly Services, St. Andrew’s Church.” Standrewstoronto.org. Accessed June 8, 2020. https://standrewstoronto.org/worship/weekly-services/

Winter, Jay. “The Generation of Memory: Reflections on the ‘Memory Boom’ in Contemporary Historical Studies.” Canadian Military History 10, no. 3, (2001): 57-66.

“48th Highlanders of Canada An Infantry Regiment of Canada’s Primary Reserves.” Canadian Armed Forces. Accessed June 16, 2020. http://48highlanders.com/01_00.html

Notes

[1] Jay Winter, “The Generation of Memory: Reflections on the ‘Memory Boom’ in Contemporary Historical Studies.” Canadian Military History 10, no. 3, (2001): 58.

[2] Bell VIII commemorates Lt. James E. Robertson, BA, Ll.B. Virtutis Gloria Merces is the motto of Clan Robertson (Donnachaidh).

[3] Winter, “Generation of Memory,” 58-59.

[4] The Queen’s Own Rifles was formerly a multi-battalion regular-force regiment, with troops based as far away as Work Point Barracks, Victoria B.C. (now part of CFB Esquimalt). The regimental depot was in Calgary.

[5] Queen’s Own Rifles Association, https://qormuseum.org/history/queens-own-rifles-association/

[6] Peter Farrugia, “A Small Truce in a Big War: The Historial de La Grande Guerre and the Interplay of History and Memory.” Canadian Military History 22, no. 2, (Spring 2013): 4.

[7] “Cross of Sacrifice,” Wikipedia, accessed June 7, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cross_of_Sacrifice

[8] “Cross of Sacrifice,” Wikia.org, accessed June 17, 2020, https://military.wikia.org/wiki/Cross_of_Sacrifice

[9] As with other Rifle Regiments, a regimental colour is not carried, with the battle honours being painted on regimental drums instead. It was announced on May 9, 2014 that the QOR has subsequently been awarded the “Afghanistan” battle honour because of the numbers of its members that had served in South-West Asia. Battle Honours of the Canadian Army – The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, accessed June 8, 2020, http://www.regimentalrogue.com/battlehonours/bathnrinf/06-qor.htm

[10] QORA

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Book of Remembrance,” The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada Regimental Museum and Archives, accessed June 8, 2020, https://qormuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/ 2019/08/book-of-remembrance.jpg

[13] A traditional toast to Fallen Comrades is given at formal military dinners.

[14] William T. Barnard, The Queen’s Own Rifles 1860-1960 (Don Mills: Ontario Publishing Company Limited, 1960), 133.

[15] John Pierce, “Constructing Memory: The Vimy Memorial.” Canadian Military History 1, no. 1, (1992): 3-4.

Paul Gough, “Canada, Conflict and Commemoration: An Appraisal of the New Canadian War Memorial in Green Park, London, and a Reflection on the Official Patronage of Canadian War Art.” Canadian Military History 5, no. 1, (Spring 1996): 30.

[16] His architectural firm, Mathers and Haldenby (1921-1991), also designed the Toronto head office buildings of Imperial Oil, Bank of Nova Scotia, and The Globe and Mail.

“Haldenby, Eric Wilson,” University of Toronto Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering, accessed June 16, 2020, https://alumni.engineering.utoronto.ca/alumni-bios/haldenby-eric-wilson/

[17] Kim Beattie, 48th Highlanders of Canada 1891-1928, (Toronto: 48th Highlanders of Canada, 1932), 425.

Gough, “Canada, Conflict and Commemoration,” 7-8.

[18] Beattie, 48th Highlanders, 425.

[19] “Sons of England Memorial,” Centre for Distance Learning and Innovation, accessed June 8, 2020, https://www.cdli.ca/monuments/on/tsons.htm

[20] “Historic Toronto,” Tayloronhistory.com, accessed June 8, 2020, https://tayloronhistory.com/tag/boer-war-monument-toronto/

[21] Beattie, 426,

“The 48th Highlanders Monument Queens Park,” Centre for Distance Learning and Innovation, accessed June 8, 2020, https://www.cdli.ca/monuments/on/toronto48.htm

[22] After WW II 10 battle honours were added in honour of 351 dead from that conflict. Like the Queen’s Own Rifles, the 48th Highlanders have subsequently been awarded a battle honour for Afghanistan.

“Battle Honours of the Canadian Army – The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada,” accessed June 8, 2020, http://www.regimentalrogue.com/battlehonours/bathnrinf/06-qor.htm

“The 48th Highlanders Monument Queens Park,” Centre for Distance Learning and Innovation, accessed June 8, 2020, https://www.cdli.ca/monuments/on/toronto48.htm

[23] “St. Andrew’s Church (Toronto),” Sensagent Corporation, accessed June 8, 2002, http://dictionary.sensagent.com/St._Andrew%27s_Church_(Toronto)/en-en/

“Weekly Services, St. Andrew’s Church,” Standrewstoronto.org, accessed June 8, 2020, https://standrewstoronto.org/worship/weekly-services/

“48th Highlanders of Canada An Infantry Regiment of Canada’s Primary Reserves,” Canadian Armed Forces, accessed June 16, 2020, http://48highlanders.com/01_00.html

“Weekly Services, St. Andrew’s Church,” Standrewstoronto.org.

[24] An architect, his other works included several buildings on the University of Toronto campus, the College Wing of Toronto General Hospital, and the “new” Centre Block on Ottawa’s Parliament Hill.

Janice Bradbeer, “Once Upon A City: Creating Toronto’s Skyline,” Toronto Star, March 24, 1016.

“John A. Pearson,” wikipedia.org, accessed June 8, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_A._Pearson

[25] Hew Strachan, The First World War. (New York: Penguin Books, 2013) 337.

[26] Farrugia, “A Small Truce,” 63

Gough, 33,

Pierre Nora. “General Introduction: Between Memory and History” in Realms of Memory vol. I trans. Arthur Goldhammer, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992): 1, cited by Farrugia, 2.

Permission is hereby granted to the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada to, with proper acknowledgement, use the following, in whole or in part, for any purpose whatsoever.