By Major Adam Saunders, CD (Ret’d) for the Maple Leaf magazine of the Central Ontario Branch of the Western Front Association.

One Colonel Hagarty, two Lieutenants D.G. Hagarty, and the 201st CEF Battalion

It seems straightforward and practical that CEF non-commissioned officers (NCOs) were assigned service numbers upon attestation to avoid confusion among the 650,000 soldiers in uniform during the First World War. Officers, however, were generally not assigned service numbers, which did not entirely prevent confusion. There were exceptions to this rule, such as when an officer attested as an NCO and was later commissioned.

There are 690 individuals named “John Smith” in the Archives Canada Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) attestation database, and 7,002 instances of the surname “Smith,” with most having their own service numbers. When researching a soldier of the Great War, obtaining a service number can save significant time and reduce confusion, especially if you’re searching for a friend’s great-uncle named Private “Smith.

One might be intrigued to learn that two individuals named “Lt. D. L. Hagarty” served in the CEF at the same time. Both were from Toronto, both stood 5′ 11 ½” (taller than the average height of 5′ 9″ in the CEF), and both served with The Queen’s Own Rifles at one point. One of the Lt. D.G. Hagartys was 36 years old upon attestation in 1914, while the other was only 21 years old when he attested in 1915. It is not difficult to imagine how their service files could have crossed paths, leading to confusion.

Dudley George Hagarty

Dudley George Hagarty attested as a lieutenant with the 3rd Battalion CEF at Valcartier on 22 September 1914. A member of The Queen’s Own Rifles, he was 36 years old and had spent nine years with the regiment. He had attended both Toronto’s Upper Canada College and Trinity College School in Port Hope, and may have been a member of their respective cadet corps. In civilian life, he sold real estate and insurance and lived with his mother at 41 Foxbar Road, Toronto. After completing his training in Salisbury, England, with the 3rd Battalion, he joined the 1st Division in France in February 1915, and witnessed the 2nd Battle of Ypres in late April 1915, serving with B Company (Coy) under Captain Muntz, who was killed early on in the battle.

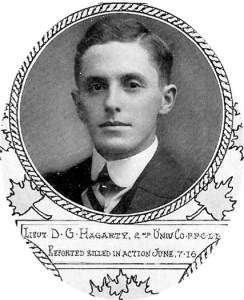

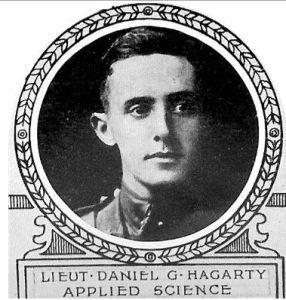

Daniel Galer Hagarty

Daniel Galer Hagarty, 21 years old, attested with the 2nd University Training Company in Montreal on 26 June 1915, despite being an engineering student at the University of Toronto. He had spent two years with The Queen’s Own Rifles, following in the footsteps of his father, Lieutenant Colonel Edward William Hagarty. Daniel lived with his parents at 662 Euclid Avenue, Toronto, and had attended Harbord Collegiate, where he also competed with cadets from around the world at the Bisley Shooting Competition.

An interesting and somewhat confusing detail in Daniel’s file is a “medical card” listing him as having been in No. 3 General Hospital in Le Treport, France, between 30 May and 7 June 1915. However, Daniel had only attested on 28 June 1915, meaning it was Dudley who was in the hospital at that time, despite the correction on the card. The correction was incorrect.

Both Hagartys were in England between July 1915 and January 1916. Daniel was with the 11th Reserve Battalion, awaiting assignment to a battalion overseas, while Dudley was with the 23rd Reserve Battalion, awaiting his next medical board. This period marked the first and predictable mix-ups involving pay.

Mix-ups and Consequences

A notable mix-up in Dudley Hagarty’s file occurs on a “promotion and appointment” form (R150), where he was to be sent to the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) on 29 January 1916. This entry was later crossed out with a note saying, “Refers to D.G. Hagarty PPCLI.” However, at that time, Dudley had already been deemed unfit for general service due to illness. This suggests that pages from the service files of the two Hagartys were actively mixed up, rather than being simple filing errors.

Dudley spent the rest of the war undergoing regular medical evaluations due to his condition (neurasthenia). He was eventually transferred to the Canadian Army Pay Corps in England, where he was promoted to captain in April 1917. Dudley returned to Canada in July 1918, deemed “surplus to requirements,” and was assigned to Militia District No. 2 in Toronto until his release in September 1919.

In Daniel’s file, several pay ledger sheets from Dudley’s file can be found, including one indicating that he was to return to Canada at his own expense aboard the SS Olympic on 5 September 1916 and had been granted leave between 8 November and 8 December 1916. The problem, of course, was that Daniel had been killed in action six months earlier. Furthermore, Daniel’s service card indicated he had been promoted to captain on 9 January 1917, despite having died six months prior.

Daniel’s Last Moments

On 2 June 1916, two days after returning from leave, Daniel was killed while leading No. 7 Platoon in No. 2 Company of the PPCLI. His platoon was positioned in the front line of the left sector at Sanctuary Wood, which was subjected to an intense bombardment by high-explosive shells and trench mortars, followed by an assault on the shelled position. Despite suffering heavy casualties, No. 2 Coy held their position (PPCLI War Diary, 2 June 1916). Daniel’s remains were recovered, so he was eventually buried at the Hooge Crater Cemetery.

On Dudley’s regimental card, it is noted that he passed through the 3rd, 9th, 17th, and 11th Bns. It was Daniel who was in the 11th while he was training in England, in anticipation of being assigned to the Patricia’s in France and Belgium. Between the two D. G. Hagartys, I am uncertain who passed through the 9th or 17th. Dudley did spend time in the 23rd Reserve Battalion while being shuffled to various commands. Along the way, he may have encountered the 9th and/or the 17th Reserve Bns, both located at Bramshott, en route to his position with the Canadian Army Pay Corps.

There were many more mixed-up pages from Dudley’s file in Daniel’s than vice versa.

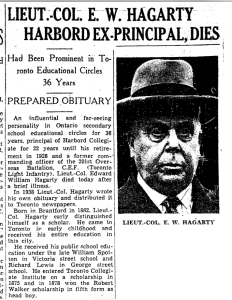

The Legacy of Edward William Hagarty and the 201st

To some degree, this is now where the story begins.

The 201st CEF Battalion, otherwise known as the “Toronto Light Infantry Battalion,” was to be raised in Toronto. Lieutenant Colonel Edward William Hagarty was offered the provisional rank of lieutenant colonel to raise and command the battalion.

Competition to fill new battalions being formed for overseas service was intense, as casualties in France and Belgium were significant. Many of the Toronto-area units being raised were closely affiliated with militia units that had recruiters in place since 1914. Battalion commanders worked tirelessly to recruit a full battalion, aiming to send them overseas as a complete unit rather than dismantling them to provide reinforcements to other battalions. Many Canadian commanding officers faced disappointment as their units were often broken up, and they were relegated to staff duties in England, or worse.

Competition to fill new battalions being formed for overseas service was intense, as casualties in France and Belgium were significant. Many of the Toronto-area units being raised were closely affiliated with militia units that had recruiters in place since 1914. Battalion commanders worked tirelessly to recruit a full battalion, aiming to send them overseas as a complete unit rather than dismantling them to provide reinforcements to other battalions. Many Canadian commanding officers faced disappointment as their units were often broken up, and they were relegated to staff duties in England, or worse.

LCol Hagarty enlisted in the still-to-be-formed 201st Battalion on 9 February 1916, at the age of 48. He resided at 662 Euclid Avenue with his wife, Charlotte, and son Daniel Galer Hagarty, who had left his studies eight months earlier to join the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) in France. LCol Hagarty was born on 7 September 1862.

Edward Hagarty was the principal of Harbord Collegiate from 1906 to 1928. His previous military experience was limited—he had served four years with The Queen’s Own Rifles (QOR) and one year as a lieutenant with the 25th (Militia) Elgin Regiment. Most of his 25 years of military experience had been spent instructing cadets in communities and high schools, and he was actively involved in various cadet organizations, including Rifle Associations. In early 1913, he was a cadet battalion commander for the Toronto Collegiate Institutes. In January 1914, he was awarded the honorary rank of lieutenant colonel in the Corps of School Cadet Instructors (CSCI). On 19 January 1916, he received a certificate confirming his provisional appointment as an honorary lieutenant colonel for the purpose of commanding a CEF battalion. He was also issued a “Certificate of Military Qualification” dated 3 June 1916 from Ottawa, endorsed by Lieutenant Colonel R. Labatt of Military District 2. This qualification appeared just as General Order 69 of 15 July 1916 was issued, authorizing the raising of several new battalions, including the 170th, 201st, and 204th.

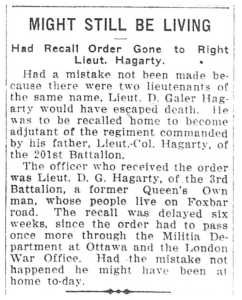

Part of LCol Hagarty’s plan was to have his son, Lt. Daniel Galer Hagarty, brought back from service overseas to become his adjutant. At this time, Daniel was completing training in England as a platoon commander with the PPCLI. Bureaucratic procedures were set in motion, and a tasking message was sent through various layers of command, according to various sources, including a newspaper article.

Part of LCol Hagarty’s plan was to have his son, Lt. Daniel Galer Hagarty, brought back from service overseas to become his adjutant. At this time, Daniel was completing training in England as a platoon commander with the PPCLI. Bureaucratic procedures were set in motion, and a tasking message was sent through various layers of command, according to various sources, including a newspaper article.

However, LCol Hagarty was devastated to learn that his son had been killed in action. He believed the military bureaucracy had mistakenly sent the order for his son to return to Canada and serve as his adjutant to the wrong person—Lt. Dudley George Hagarty, his son’s namesake. LCol Hagarty felt that had the message been sent to his son, Daniel, he would have “escaped death.” The loss of his son, combined with the inability to recruit sufficient soldiers from the cadet programs he had nurtured for years, led to the 201st Battalion being broken up while still in Canada. The soldiers were reassigned to the 170th Mississauga Horse (10th Royal Grenadiers) Battalion and the 198th Canadian Buffs (QOR) Battalion. It did not help that LCol Hagarty had declared his battalion the “temperance battalion,” which may have hindered recruiting efforts somewhat.

While I have not yet found a nominal roll for the 201st Battalion, the allocated block of service numbers (228001–231000) presented themselves. Unfortunately, the 201st did not attract enough recruits, especially when compared to other Toronto-area battalions. LCol Hagarty’s resignation was likely the final blow to any future the battalion might have had. It is not hard to imagine the sense of personal disappointment LCol Hagarty must have felt. Resigning under such circumstances would have been a very public statement of his frustration.

LCol Edward William Hagarty resigned from command of the 201st Battalion on 4 September 1916, just three months after the death of his son. Even if he had managed to take the 201st Battalion to England, his military experience at the senior officer level was nonexistent. On LCol Hagarty’s “Last Pay Certificate,” it was clearly noted that his “provisional appointment was cancelled.”

In late July 1919, LCol Hagarty and his wife Charlotte visited the battlefield in Belgium where their son fell. They found his grave at the Hooge Crater Cemetery before returning to Canada aboard the SS Savoie.

Legacy

Edward and Charlotte left a lasting legacy in Toronto with the establishment of the imposing Memorial at Harbord Collegiate Institute, which was dedicated in 1921 to “These former pupils who died for humanity in the Great War of 1914-1919.” Sadly, 20 years later, 52 more names would be added to the memorial.

Edward and Charlotte left a lasting legacy in Toronto with the establishment of the imposing Memorial at Harbord Collegiate Institute, which was dedicated in 1921 to “These former pupils who died for humanity in the Great War of 1914-1919.” Sadly, 20 years later, 52 more names would be added to the memorial.

Another lasting tribute is from the University of Toronto website as “the Reginald & Galer Hagarty Scholarship established by LCol E.W. Hagarty and Charlotte Ellen Hagarty in memory of their sons, Reginald and Galer. The scholarship is awarded to students entering their first year of any undergraduate program at the University of Toronto, based on academic achievement. The recipient must be a graduate of Harbord Collegiate.”

Edward passed away on 2 March 1943 and is buried in the family plot at St. James Cemetery in Toronto, alongside his wife Charlotte, who passed away two months later. Both of their sons are commemorated on the memorial at Harbord Collegiate.